Diluting DORA: How Marketers and Consultants Bastardize Engineering Best Practices

Table of Contents

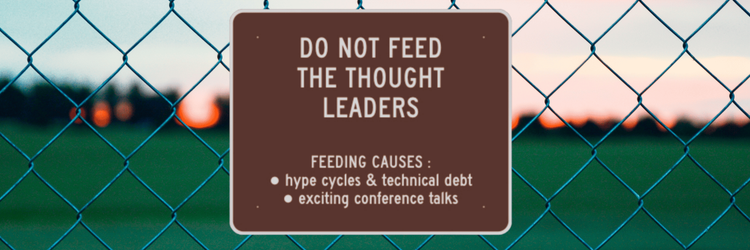

Marketers and consultants are scummy. They try to make you think they have the answers to the problems you and your business are running into by telling half-truths that have a foundation in technical best practices, but they don’t actually have the answers to these complex problems.

I have a somewhat unique and fairly thorough understanding of how marketers and consultants do this, how they take useful technical best practices and bastardize them for their own gain. I have a Computer Science degree and started my career as a computer programmer. I moved up into a system administrator role – the spiritual predecessor to DevOps roles. Eventually, I decided to get an MBA and worked for Deloitte as a senior consultant and eventually manager on tech projects afterward. After Deloitte, I moved into product marketing, working at DirecTV and then at several tech companies including New Relic, Twilio Segment, and, now, Earthly. I have been the user, the buyer, the marketer, and the consultant at different points in my career. I’ve seen this pattern repeated over and over.

In this post, I’m going to focus specifically on DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA), what it is, why it matters, how marketers and consultants abuse it, and the negative impacts that abuse causes.

Understanding DORA

DORA started as a collaboration between a small group of researchers and Puppet – one of the first DevOps tools on the market. They researched and gathered data from a wide swath of companies about their software development and delivery processes, producing the State of DevOps Report – one of the earliest and by far the most trusted reports on DevOps – from 2014 to 2017. The 2018 State of DevOps Report was noticeable sans Puppet but had a new diamond sponsor, Google. The company eventually acquired DORA in 2019, and they have continued to research and publish the State of DevOps Report every year since under the Google Cloud and DORA banners.

You can learn more about DORA’s history in co-founder Jez Humble’s 2019 blog post, “DORA’s Journey: An Exploration”.

From the very earliest State of DevOps Reports, one of the primary takeaways is that companies with better IT performance are more productive, more profitable, and have a higher market share.

“Our data shows that IT performance and well-known DevOps practices, such as those that enable continuous delivery, are predictive of organizational performance. As IT performance increases, profitability, market share and productivity also increase.” - 2014 State of DevOps Report

The report included three metrics used to measure IT performance:

- Deployment frequency

- Lead time for changes

- Mean time to recover from failure

DORA has since expanded this to four metrics:

- Deployment frequency

- Lead time for changes

- Time to restore service

- Change failure rate

Each State of DevOps report includes a lot of information and research on what it takes to meaningfully improve these metrics, including tooling that helps measure and/or improve these metrics and a heavy emphasis on the organizational culture needed to perform well and improve. It looks at large systemic changes that teams can make to help improve IT performance and encourages measuring that performance according to this set of metrics.

It’s difficult to explain how impactful DORA’s approach to DevOps and especially the DORA metrics have been. Every company that makes Observability (previously known as Monitoring) tooling anchors on the DORA metrics. Almost every best practice regarding DevOps anchors on DORA metrics. It’s difficult to find individual success stories, because the use of DORA metrics is so widespread now that no one success story seems like a big deal. Every success story on every observability or DevOps tool website is a story of the success of DORA.

This success and the trust that DORA has gained, especially the success of the DORA metrics, has made it a ripe vehicle to disguise selling snake oil and bullshit. The DORA metrics seem like a straightforward path to success, but, if you read the reports beyond just the metrics, it clearly isn’t. The path to improving your company’s DORA metrics was never prescriptive in any of the reports, and that’s because it usually involves deep cultural change in an IT or Engineering organization. There is no cookie-cutter approach to organizational change. It’s difficult and unique to each organization. Having simple, easy-to-measure metrics as goals and an ambiguous path to get there leaves a lot of room to create imaginary solutions and sell people things that may or may not help them.

How Marketers Abuse DORA

Not All Marketing Is Bad

I’m going to give marketers a lot of credit for popularizing useful technical best practices like those espoused by DORA. Make no mistake that Puppet’s involvement in the original and first few State of DevOps Reports wasn’t wholly altruistic. Those reports were incredibly strong validation that the processes Puppet promoted and the tools that they built could make your IT operations better and, in turn, improve your business performance. And they helped produce the reports, not just as a sponsor from my understanding. So of course they were going to use these reports for marketing and sales purposes. There’s nothing wrong with that. I consider this an example of good marketing – spreading knowledge and best practices that are not specific to the product your company makes and then showing how your product helps enable those best practices.

Marketers do a lot of good things that follow this pattern. They create and sponsor reports, like Google prior to acquiring DORA and like CircleCI, GitLab, Deloitte, and many others that sponsored the most recent State of DevOps Report. They create and sponsor organizations and events – such as the Cloud Native Computing Foundation and KubeCon. They spend time and money doing a bunch of other things that are beneficial and also work as marketing.

When I was the product marketer for the open source program at New Relic, I put together and the company executed a marketing program that sponsored the Oregon State University Open Source Lab, made a grant to freeCodeCamp for them to create a course on OpenTelemetry (that has been viewed 190k times, nice!), sponsored multiple tech podcasts, and started the company’s GitHub Sponsors program that has now sponsored over 70 developers and organizations (do you have any idea how difficult it is to get a corporate procurement manager to give you approval to spend $5K on donations to individuals through one of GitHub’s then-beta features?). Every item on that list is a good thing in my opinion. Every item on that list also works as marketing.

Where Marketers Go Bad

Where marketers go bad is when they start trying to make you believe that the product they’re pitching will solve problems it can’t. For example, if an observability tool vendor claims that their tool can increase your deployment frequency, reduce your lead time for changes, reduce your time to restore service, and/or reduce your change failure rate, those marketers are promising solutions to problems their tool couldn’t possibly solve. I don’t think any observability vendors make claims like this anymore, because they understand it’s ludicrous.

The more common thing you’ll see marketers do in this vein is to create “marketing solutions” that promise to solve difficult business problems by following a set of handy steps, but, in reality, the problems are much more complicated than a few standard steps can solve. The insidious thing about the marketing solutions is that a lot of them are legit. Determining if one is worth your time or not isn’t easy though. You have to figure out if a marketing solution is selling the answer to a technical problem or an organizational one. If it solves a technical problem – e.g. how to use our tool on AWS – there’s a good chance it’s legit. If it solves an industry-specific, non-organizational problem – e.g. how to deploy a managed version of our tool into a private VPC for industries with high security requirements – there’s a good chance it’s legit.

If a marketing solution promises to solve an organizational problem, if it solves a technical problem but a non-trivial portion of it is devoted to organizational problems, or if any part of the solution relies on assisted or unassisted organizational change, don’t believe what they are selling. These types of solutions are frequently more marketing hype than value. They promise to solve a big, organization-wide problem by following a specific set of steps that the vendor has totally tried out with other customers and not just made up. Sometimes they even promise (or at least hint) that their solution will create the organizational change required to solve these organization-wide problems. These solutions are rarely truly successful, but they require a lot of professional services hours and generate a lot of revenue anyway.

For DORA, this exhibits itself by observability tool vendors creating solutions for things like DevOps or Cloud Adoption – things that require organizational change. They use DORA’s State of DevOps Report and the DORA metrics to shape the steps in their solutions and the pitches they make to customers.

The result is frequently a hefty amount of instrumentation that leaves the customer more locked into the vendor’s tool (although this is getting less prevalent with OpenTelemetry), a bag of dashboards that show DORA metrics alongside a smattering of other metrics the vendor’s solution deems important, and a fat bill.

How Consultants Abuse DORA

Consultants Are Smart, and Sometimes You Need Them

I’m not as generous in my assessment of consultants as I am in my assessment of marketers. This is from my personal experience being both a tech consultant at a major consultancy and a marketer at companies of all sizes, from early-stage startups to huge conglomerates. Consultants do much less good than marketers, and they build their entire business around solutions, the same area that marketers run afoul of abusing technical best practices.

So here’s the part where I tell you the pros of consultants. They sponsor a lot of the same technical reports, organizations, events, content creators, etc., as marketers. They also produce a lot of research-heavy reports that have useful info (unfortunately, they also produce a lot of sales pitches disguised as reports). Consultants probably do the best job of spreading technical best practices across industries, because they jump around industries so often. Sometimes you need a consultant because you need an outside perspective, you want advice from people with experience in areas your team is lacking, or you don’t want to hire people full-time for temporary roles for work that is project-based or non-recurring. I can also say with certainty that my co-workers when I was a consultant were, for the most part, some of the most intelligent, well-rounded, well-composed people I’ve ever met in my life. If you need to put together an Academic Decathlon team or want to get the best tutors to get your child through high school and college with straight A’s, consultants are the way to go.

Where Consultants Go Bad

Consultants go bad the same way marketers go bad, with solutions. That’s all consultants sell though. Sometimes it’s a fully-composed solution with defined steps, sometimes it’s a hand-wavey framework that is used as a guide to a project, sometimes it’s architecting and building completely custom systems. Consultants have made an industry out of the same practices that stain marketers’ reputations, trying to make you believe that the solution they’re pitching will solve your problems, regardless of whether it can or can’t.

A consultant is like a marketer cross-bred with a 1980s professional wrestler who’s amped through the roof on amphetamines and anabolics. They’re on the road non-stop for years, say whatever they need to earn a buck, have questionable ability to execute on what they promise, and frequently end up divorced and/or in rehab before they’re forty. This lifestyle, much like that of professional wrestlers, often leads to short-term decision-making, both for them and their clients. Consultants generally only last two to four years at top firms too (they are pretty terrible jobs), and they have aggressive sales and utilization quotas to hit. Sometimes, closing a $500K contract at the end of the sales year for less than necessary work will get them an extra $5K in their annual bonus this year, which very well could be worth more than an additional $20K on your bonus next year, because you can never tell if you’ll be there next year as a consultant. Once again, consultants are smart. They understand their incentive structure and how to work towards their incentives. Sometimes that leads to bad behavior like selling useless work or prioritizing short-term gains over long-term relationships with their customers.

For DORA, this exhibits itself by consulting companies creating drivel like this from McKinsey, “Yes, you can measure software developer productivity” (the inspiration for this post). McKinsey is far from the only consulting company to push solutions like this one, ostensibly for the technology, media, and communications industries. Every consulting company has some version of this solution that they sell. This one takes DORA metrics, adds in SPACE metrics to measure developer productivity (developed by GitHub, Microsoft Research, and the University of Victoria), and then adds in some custom McKinsey-curated metrics that are supposed to “… identify what can be done to improve how products are delivered and what those improvements are worth, without the need for heavy instrumentation.”

Are your BS meters beeping like crazy right now? Let’s see, this solution promises to solve an organization problem, requires a large number of metrics that you need to collect for it to function properly, and you have no good way of measuring ~50% of them because they can’t be instrumented. The beauty of DORA metrics is that they are constrained and they can be measured precisely (through instrumentation). This solution that this consulting company is selling sounds like you’re getting a bag of semi-related, occasionally useful metrics with a project that is a nightmare during requirements, drowning in change requests and additional billings, and results in something pretty to look at but not the organizational change you needed.

Help Stop the Dilution of DORA

DORA’s annual State of DevOps Report and the metrics they’ve developed to improve IT performance are extremely useful and widely adopted. There isn’t a ton of argument about the efficacy of improving DORA metrics. There is a lot of disagreement on how to get to the point that your team can efficiently monitor and improve DORA metrics though. That’s because it requires organizational change, and organizational change isn’t cookie-cutter. Marketers and consultants capitalize on this ambiguity and create solutions promised to improve your DORA metrics. No matter what they say though, their solutions will never be able to consistently cause the organizational change promised by them. The organizational change required for DevOps to thrive and for DORA metrics to be their most useful has to come from within an organization. You can’t outsource it or ask an outsider to do it for you, because the hard part isn’t the right tool or metric, but the people and processes.

So, what can be done to help prevent this recurrent bastardization of technical best practices? I could make an impassioned plea to all of the decent, honest marketers and consultants out there (the majority of both are decent and honest), but that wouldn’t get the job done. It doesn’t matter how honest and decent marketers and consultants are, their behavior will follow their incentives, and their incentives are too perverse. The sale is what matters most to both of these groups as a whole, not the efficacy of the solutions they provide. So asking these groups or even individuals in these groups to change their behavior is pointless.

It’s on you, the technical professionals – developers, DevOps engineers, SREs, engineering managers, all the way up to CTOs – to remove the incentive marketers and consultants have to develop BS solutions. Be critical about research, reports, or other content developed or contributed to by marketers and consultants. Ask if the solutions marketers and consultants are trying to sell you require organizational change. If it does, don’t buy anything. Ask if they are selling work that isn’t transient, that should be done by a full-time employee. If they are, don’t buy anything. Ask if the solution they are selling sounds feasible and reasonable. If it doesn’t, you should not buy anything and ask a lot more questions. When it comes to marketers and consultants (and, honestly, so many other people in life), be skeptical, be critical, and don’t believe anything that sounds too good to be true.

Turn your engineering standards into automated guardrails that provide feedback directly in pull requests, with 100+ guardrails included out of the box and support for the tools and CI/CD systems you already have.