Build Your Own Ngrok Clone With AWS

Table of Contents

Explore DIY ngrok alternatives in this article. Earthly provides a route to efficient, reproducible builds. Learn how.

Introduction

ngrok is a tool that allows you to create secure, publicly accessible URLs for your locally running code. Just a simple ./ngrok http 3000, and your tunnel is up and running! It also comes with an inspector for all traffic traveling over its tunnels. Pretty slick right? However, for a stable domain it costs at least $5/month, and it only goes up from there. Additionally, you’re limited in the number of connections and tunnels that you can make.

However, it can be hard to trust fancy tools like ngrok until you experience how the sausage is made; at least once. It may also be hard to explain yet another recurring charge on the credit card to your partner. So, here is a tutorial to build yourself a DIY ngrok for free (at least 12 months, after that its very cheap), using the AWS Free Tier, Nginx, and (of course) Earthly. The result is a decent approximation that won’t break the bank.

So, How Does ngrok Work?

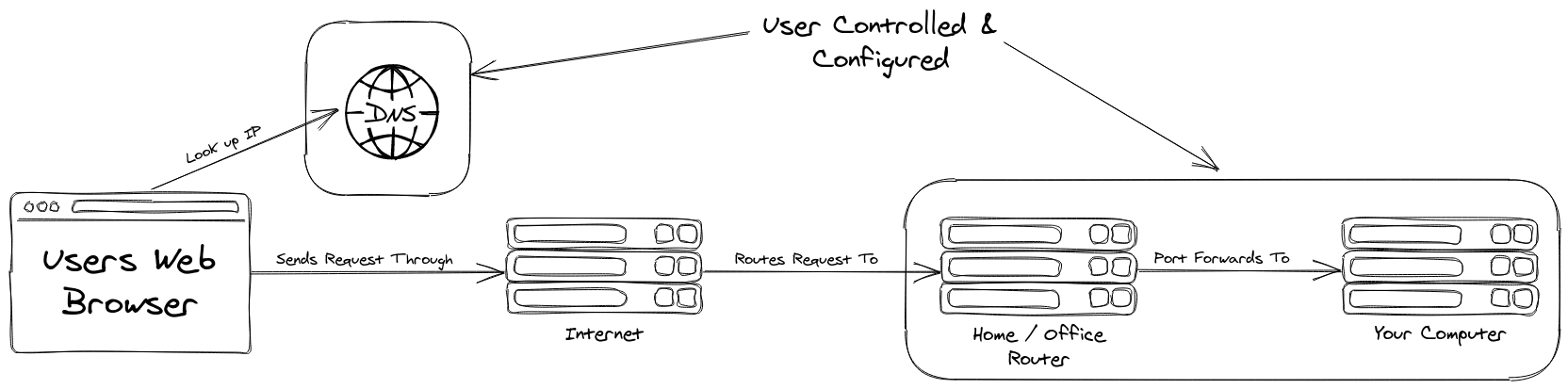

To understand why ngrok is so cool, you’ll need to first understand how you would normally get traffic from the broader internet into your local machine. A typical flow would be something like this:

This flow is normal for most of the machines on the internet today, but it has its downsides for local development. For instance, most home and non-commerical internet connections do not have a Static IP - which means you need to double-check your IP address before sending it out, or (more often) install and configure additional software to keep your DNS records up to date.

Additionally, you’ll need to configure your router to forward that traffic to your machine. This configuration is typically fairly annoying to set up, and should also be turned off each time you aren’t using it, otherwise you are keeping your computer exposed to the internet at large! Its like putting a giant welcome mat out for hackers during their automated scans.

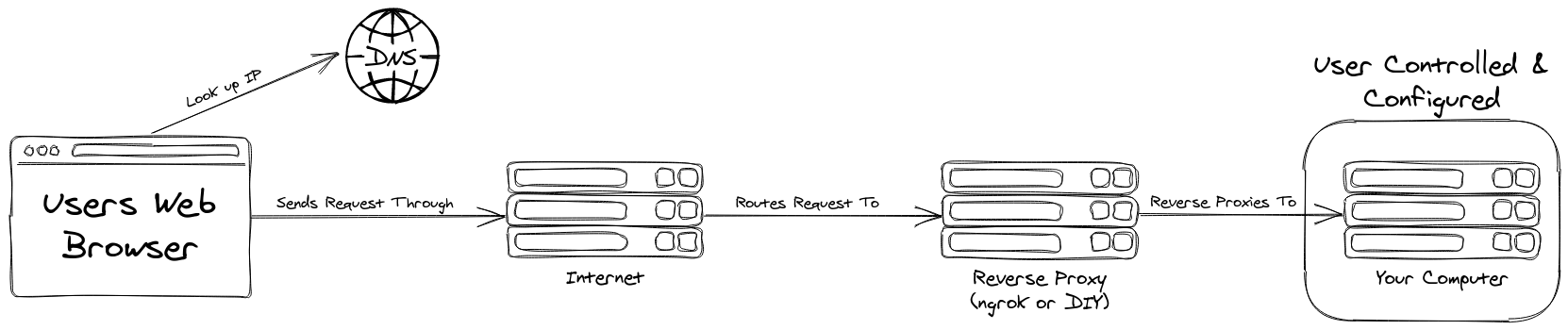

With this foundation, you can now understand whyngrok (and our DIY one) is so cool! It removes the need for all this additional configuration, while also providing better security. All you need to do is add an extra computer into the mix, like this:

Because you are using a Reverse Proxy to get the traffic from the extra computer to yours, no additional configuration is required on your end. And, when you are done, you can simply shut down the extra machine, and there are no loose ends or open ports left to close!

As mentioned above, this tutorial uses AWS to create the proxy. Other cloud providers will work just as well, but the commands and samples in this document will be for AWS only. Pull requests are welcome, if you want to contribute specific scripts for your cloud provider of choice!

One elephant in the room to address before moving on is the inevitable “Why not (Terraform/Pulumi/Cloud Formation/My Favorite IAAS tool…)?” question. These tools are, in fact, made for setting up and tearing down infrastructure exactly like this! However, using fewer tools helps keep this tutorial simple and accessible, so only the AWS CLI will be used throughout.

Lets Build It

You will need the following to complete the rest of this tutorial:

- An active AWS account (If you don’t have one, you can sign up on aws)

- Installed the AWS CLI

- Configured AWS credentials

Optionally, you may also want to install:

With those in hand, it’s time to get started!

Where Will the Instance Live?

Before creating anything in the cloud, you’ll need to make sure that you have some information about the VPC and subnet the instance will be assigned to. This information can be found in the console, or on the command-line via aws ec2 describe-subnets. It will list all your subnets, and the VPCs they belong to.

If your cloud is like most peoples, you likely have quite a few of these lying around, which makes it difficult to find the one you want to place your proxy in. I like to add jq into the mix to make it easier to parse, like this:

❯ aws ec2 describe-subnets \

| jq -r '.Subnets[] \

| "\(.AvailabilityZone)\t\(.CidrBlock)\t\(.SubnetId)\t\(.VpcId)"' \

| sortWhen selecting a subnet, ensure that the one you choose assigns public IP addresses, as you will need to accept traffic from the general internet later.

SSH Key Pair

The first thing to create is your EC2 SSH key pair. This is simple to do, especially because the aws tool can generate on for you.

❯ aws ec2 create-key-pair \

--key-name proxy-key-pair \

> key-output.json❗ About the AWS CLI Output

Note the > key-output.json at the end. The aws CLI tool will always invoke your system pager with some kind of JSON output as the result of any calls. Because you don’t want to lose the key generated by aws for our yet-to-be-created instance, capture it here. It’s a running trend that you will see throughout this tutorial.

You can get the key directly with jq by jq -r .KeyPairId key-output.json, or via your preferred means.

Security Group

Now that you have a key pair, you will also need to create a security group for the instance to reside in. To oversimplify, a security group is essentially a firewall for your instance, constraining what ports traffic is allowed to enter or leave on. You can read more about security groups on aws, for a longer and more complete explanation. Getting this right is important, so your proxy is less likely to be compromised.

❯ aws ec2 create-security-group \

--group-name reverse-proxy \

--description reverse-proxy \

--vpc-id $VPC_ID \

> sg-output.json❗ Don’t Forget

Make sure you replace $VPC_ID with the ID for the VPC you identified earlier.

By default, AWS security groups are configured to disallow all traffic coming in (ingress), and to allow all traffic out (egress). While an instance that doesn’t allow traffic in is fairly secure, it also doesn’t do you much good. You will need to open up port 22 (ssh) for traffic from our current IP only, and port 80 (HTTP) for traffic from the internet at large. By restricting SSH to your current IP address, you prevent external entities from attempting to SSH into your proxy.

❯ aws ec2 authorize-security-group-ingress \

--group-id $SG_ID \

--protocol tcp \

--port 22 \

--cidr $IP/32 \

--no-cli-pager

❯ aws ec2 authorize-security-group-ingress \

--group-id $SG_ID \

--protocol tcp \

--port 80 \

--cidr 0.0.0.0/0 \

--no-cli-pagerFind Your Public IP From the Command Line

AWS has a public service that returns your IP to you. It’s super handy for scripting, because its much clearer to read than the most popular dig-based examples passed around on the internet. You can use it like this: curl -s https://checkip.amazonaws.com

❗ Don’t Forget

Make sure you replace $SG_ID with the ID for the security group you created earlier. If you saved the output like the sample earlier, you can get it by running jq -r .GroupId sg-output.json. Also, make sure you replace $IP with your public IP address.

EC2 Instance

Now that you have keys, and a security group configured in AWS, you’re finally ready to create your EC2 instance! Its easiest for this kind of work to use a t2.micro, since that is available on AWS’ free tier. If your account is older than 1 year, this instance is still among the cheapest to provision. If a t2.micro is too expensive, you may want to size down to a t2.nano, or consider spot instances, which are beyond the scope of this tutorial. The instance will be provisioned with an AMI using Amazon Linux 2, to keep things as simple as possible.

❯ aws ec2 run-instances \

--image-id resolve:ssm:/aws/service/ami-amazon-linux-latest/amzn2-ami-hvm-x86_64-gp2 \

--count 1 \

--instance-type t2.micro \

--key-name $KEY_NAME \

--security-group-ids $SG_ID \

--subnet-id $SUBNET_ID \

> ec2-output.json❗ Don’t Forget

Make sure you replace $KEY_NAME with the name (not id) of the key pair you created earlier (proxy-key-pair). Also make sure you replace $SG_ID with the ID for the security group you created earlier, and $SUBNET_ID with the subnet you identified before you began.

EC2 Is Fast, but Not Instant

Although AWS can provision instances very quickly, it can still take a couple minutes for the instance to come up, so be patient! You can wait for the instance on the CLI (if desired) by running the following command: aws ec2 wait instance-status-ok --instance-ids $EC2_ID, where $EC2_ID is the instance ID from the prior step.

Creating the instance isn’t the end of our work, however. You’ll still need to configure it to actually reverse proxy the traffic coming in from the internet to our local development machine. To that end, Nginx is a fantastic,battle-tested option. As soon the instance is ready, SSH into the box and install Nginx.

❯ sudo amazon-linux-extras install nginx1Nginx needs to be configured to use the AWS-assigned public DNS name, and proxy traffic from port 80 to you. Heres a sample config you can use:

upstream tunnel {

server 127.0.0.1:8080;

}

server {

server_name PUBLIC_DNS;

location / {

proxy_set_header X-Real-IP $remote_addr;

proxy_set_header X-Forwarded-For $proxy_add_x_forwarded_for;

proxy_set_header Host $http_host;

proxy_redirect off;

proxy_pass http://tunnel;

}

}❗ Don’t Forget

Be sure to replace PUBLIC_DNS with the AWS public DNS name. This is not in the initial output from AWS, because the DNS name is not granted until the machine enters a running state. You can find it by running aws ec2 describe-instances --instance-ids $EC2_ID, where $EC2_ID is the ID of the machine you provisioned earlier. This ID can be found in the output when you created the instance by running jq -r '.Instances[0].InstanceId' ec2-output.json

Save the completed configuration as /etc/nginx/conf.d/server.conf.

Additionally, Nginx doesn’t quite handle the lengthy public DNS names that AWS hands out, so you’ll need to increase server_names_hash_bucket_size to the next power of 2, which is 128. To do this, add server_names_hash_bucket_size 128 to /etc/nginx/nginx.conf, in the http section.

Now that Nginx is configured, start it, and exit your SSH session.

❯ sudo service nginx start

...

❯ exitUsing the Proxy

Now that the instance is configured, all you will need to do to allow the internet at large to connect to a service running on your local box is to use an ssh reverse proxy to get data from AWS to your local machine! Start one up like this:

❯ ssh -i key.pem -R 8080:localhost:$LOCAL_PORT ec2-user@$PUBLIC_DNS❗ Don’t Forget

Replace $LOCAL_PORT with the port your application is running on, and $PUBLIC_DNS with the AWS-assigned public DNS name, like you did for the Nginx config.

Once that is up, all you need to do is simply share the AWS public DNS name with anybody you want to allow into your locally-hosted website!

Teardown

Although you can leave the proxy up for as long as you like, you’ll likely need to tear it down eventually. If you have AWS console access, simply terminate the instance, delete the security group, and delete the key pair. If you saved the IDs of these resources (they are in the JSON responses from earlier), you can also do it via the command line:

❯ aws ec2 terminate-instances --no-cli-pager --instance-ids $EC2_ID > /dev/null

❯ aws ec2 delete-key-pair --no-cli-pager --key-pair-id $KEY_ID && \

aws ec2 delete-security-group --no-cli-pager --group-id $SG_IDNote that the instance could take a couple minutes to finish terminating. You will not be able to remove the key or security group before the instance has been terminated.

Create Using Earthly

If you don’t want to deal with manual setup or teardown, we’ve created an Earthfile that should automate all of this for you. It can create a proxy just like this, from scratch, in under five minutes! To start up a proxy using earthly, execute this single command.

❯ earthly \

--secret-file config=/home/user/.aws/config \

--secret-file credentials=/home/dchw/.aws/credentials \

--build-arg AWS_REGION=my_region \

--build-arg SUBNET_ID=my_subnet \

github.com/earthly/example-diy-ngrok:main+build-proxyAWS Credentials

The reason you’ll need to pass the credentials, is so that our scripts can use them to construct the proxy. If you are uncomfortable passing credentials to a remote target, feel free to clone and inspect the repository before using it. You could also simplify this by trying out Earthly’s experimental cloud-based secrets.

❗ Don’t Forget

Replace the following:

/home/user with the directory of the AWS configuration directory (.aws)

my-region with the AWS region you use.

my-subnet with the ID of the subnet you would like to use.

If you need to use temporary role-based credentials, add --build-arg AWS_PROFILE=my_profile, where the profile is the one to assume when creating the resources.

Building this container will construct a proxy in the same manner detailed earlier, but with a few extra benefits:

- Allows you to retrieve the generated SSH key

- Automated teardown of the constructed proxy

- Sample SSH Command for proxying

- A list of all IDs for all resources created

To see everything it can do, run docker run proxy:latest for a list.

Shortcomings

This approach to a free, simple ngrok alternative isn’t without its shortcomings. For instance, it can’t do https without a self-signed certificate, because issuers like Let’s Encrypt won’t issue certificates for AWS public DNS names. Also, it can’t handle a ton of traffic since its a small t2.micro capped at low bandwidth.

It also requires non-trivial IAM permissions in AWS to set up and tear down. If you don’t have that kind of access to an account, you may end up waiting on others to set it up for you.

Conclusion

Turns out it’s pretty simple to get something basic up and running, just like ngrok does. But, if you find yourself relying on this kind of tooling every day, it may be better to pay for a service that can do it better.

Thanks for following along with us! Visit the example repository, with all scripts available on GitHub.