Static and Dynamic Linking Explained

Table of Contents

This article explains how to handle linking in programming. Earthly simplifies the process of building and integrating static and dynamic libraries for C and C++ developers. Learn more about Earthly.

Have you ever wondered how your code can call a library function like printf() and the system can locate it instantly? It may seem like magic, but there’s a lot more going on behind the scenes. In fact, it all works because of a process called linking, which plays a crucial role in the compilation process of programming languages like C and C++.

When you write a program in a compiled language, such as C or C++, the code goes through several stages before it can be executed by the computer (more on these stages in the next section).

Linking can be accomplished via two methods: static linking at compile time or dynamic linking at runtime. In this article, you’ll learn about both types of linking and how they work. In addition, you’ll learn how to create and effectively use static and dynamic libraries. But let’s start by outlining the compilation process.

The Compilation Process

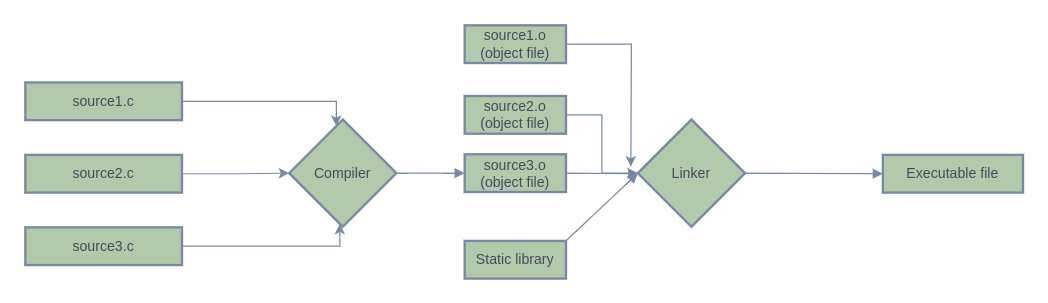

The compilation process begins with the source code, which is a human-readable representation of your program. The source code is then fed into a compiler, which translates the code into instructions known as object code. The output of this stage is one or more object files, each containing a portion of the program’s machine code.

However, programs often rely on external code libraries to provide additional functionality. These libraries contain pre-compiled code that can be reused by other programs. The object files generated from your source code may have references to functions or variables defined in these external libraries.

This is where linking comes into play. Linking is the process of resolving all variables and function call references in the object code to their respective definitions, which may be located in external libraries.

To put it simply, linking is like connecting the pieces of a puzzle. It ensures that all the required components of your program, including the code from external libraries, are brought together so that the computer can run the program.

This linking is can be static linking or dynamic linking.

What Is Static Linking?

Static linking is a technique in which all the required code and libraries for a program are combined into a single executable file during compile time. With static linking, the actual code of the external libraries (also known as static libraries) is directly incorporated into the final executable.

The resulting executable file contains all the necessary code and dependencies, ensuring that the program can run independently without requiring any external files or libraries at runtime. In other words, static linking creates a self-contained program that doesn’t rely on any external resources when executed.

To illustrate static linking, let’s create a basic C program for a project. You need the following prerequisites before you get started:

- A C compiler, such as the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) or Clang. Most Linux distributions including Ubuntu and Fedora come preinstalled with

gcc; however, if you’re using macOS,clangis the preferred C compiler. To check if it’s installed, open a terminal window and run theclangcommand. If it’s not currently installed, run the commandxcode-select --installto install it. - CMake, an open source platform-independent build system, to build the program.

All the code for this tutorial is available in this GitHub repo.

Static Linking Example

This example will demonstrate how static linking works by showing the process of compiling and linking C code using CMake, a build system generator.

Start by creating a directory called linking_explained for your project:

$ mkdir linking_explained

$ cd linking_explainedThen create a new file called add.c:

int add(int a, int b)

{

return a + b;

}And create a file named main.c:

int add(int, int); // the prototype for add

// global variables

int x = 10;

int y = 20;

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

int sum = add(x, y);

return sum;

}In this code, add.c contains the function add which takes two integers and returns their sum. The main.c file calls theadd function.

Next, build this project using CMake. To do that, you need to add a file called CMakeLists.txt with the following content:

# minimum CMake version required to build our project

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.10)

# Set the project name as linking_explained

project(linking_explained)

# add an executable with name "main", which depends on main.c and add.c

add_executable(main main.c add.c)To build the project, run the following commands:

$ cmake .

$ cmake --build .The first command generates the build files, and the second command runs the build using the generated build files.

The second command’s output should look like this:

Scanning dependencies of target main

[ 33%] Building C object CMakeFiles/main.dir/main.c.o

[ 66%] Building C object CMakeFiles/main.dir/add.c.o

[100%] Linking C executable main

[100%] Built target mainWhen you compile this project, the compiler creates individual object files (main.o and add.o) containing machine code for each C file. Since the main.c file doesn’t define the add function, the compiler leaves it undefined in the main.o file.

In the next step, the linker performs linking by resolving any missing information. It checks object files for undefined symbols and locates their definitions in other object files or libraries. In this case, the main.o file has one undefined symbol (ie the add function). Since in the CMakeLists.txt file we added the main.c and add.c files as the dependencies of the main program (via the add_executable command), the linker searches for the definition of the add function in those dependencies and finds it in add.o object file. Next, the linker combines those two files into a single file, which results in the final executable with resolved symbols and final memory addresses.

To experiment a little more, try to remove add.c from the add_executable command in CMakeLists.txt and then build it again:

$ cmake .

$ cmake --build .Output:

Scanning dependencies of target main

[ 50%] Linking C executable main

/usr/bin/ld: CMakeFiles/main.dir/main.c.o: in function `main':

main.c:(.text+0x24): undefined reference to `add'

collect2: error: ld returned 1 exit status

make[2]: *** [CMakeFiles/main.dir/build.make:84: main] Error 1

make[1]: *** [CMakeFiles/Makefile2:76: CMakeFiles/main.dir/all] Error 2

make: *** [Makefile:84: all] Error 2As you can see, you get an error message:

undefined reference to `add'Since you haven’t added add.c as a dependency, the linker is unable to find a definition for the add function, and it can’t perform the linking.

Statically Linked Libraries

Now that you know how static linking works, let’s dive into static libraries. Libraries are collections of reusable code that can be utilized in a project instead of duplicating the same code.

Just like linking, there are two types of libraries: static and dynamic libraries. Static libraries are linked to the executable using static linking. In this section, you’ll create a static library and link it to your main program.

Start by adding another file called sub.c to your project, which contains the following code:

int sub(int a, int b)

{

return a - b;

}You can create a library called libint using the add.c and sub.c files. Creating a library will allow you to group similar files (such as those containing mathematical operations) in one place and link them with other programs with a single command. To do this, you need to make the following changes to your CMakeLists.txt file:

# The minimum CMake version required to build this project

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.10)

# Project name

project(linking_demo)

# Create a static library from the source files

add_library(libint STATIC add.c sub.c)

# Set the library output name as libint

set_target_properties(libint PROPERTIES OUTPUT_NAME int)

# Set the library output directory

set_target_properties(libint PROPERTIES ARCHIVE_OUTPUT_DIRECTORY \

${CMAKE_CURRENT_BINARY_DIR}/lib)

# Add the include directory for the library to access necessary header files

target_include_directories(libint PUBLIC ${CMAKE_CURRENT_SOURCE_DIR})

# Create an executable from main.c and link it to the library

add_executable(main main.c)

target_link_libraries(main libint)Here, you added a static library called libint with add.c and sub.c as sources, and you specified the output file name as int. You also specified the include directory, which allows it to access any required header files needed by the libint target. Header files are files containing global variables and function prototypes (such as the prototype you created for add.c in main.c previously) that helped the linker identify and locate the functions that will be imported in the libraries. In this case, libint depends on the add and sub functions located in the add.c and sub.c files in the current working directory. That’s why the current working directory has been added as a directory for the libint target.

To build the project, run the following commands:

$ cmake .

$ cmake --build .You should see the following output:

Scanning dependencies of target libint

[ 20%] Building C object CMakeFiles/libint.dir/add.c.o

[ 40%] Building C object CMakeFiles/libint.dir/sub.c.o

[ 60%] Linking C static library lib/libint.a

[ 60%] Built target libint

Scanning dependencies of target main

[ 80%] Building C object CMakeFiles/main.dir/main.c.o

[100%] Linking C executable main

[100%] Built target mainIn this code, the object files are generated for the add.c and sub.c files, which are combined to create the static library: libint.a. You’ll notice that the generated file has the extension .a. This is the standard extension in C for static libraries on Linux and is short for “archive”. On Windows, static libraries typically carry the extension .lib. Once the static library is created, the main executable is linked to the library.

What Happens When You Link to a Static Library?

Static libraries, also known as archive files, are packages of code that are compiled and linked directly to the target program. To create a static library, you need to compile its C source files (ie add.c and sub.c) into object files and then package these object files into an archive file. The static library created in the previous example is called libint.a and consists of add.o and sub.o files.

CMake simplifies the process of generating a static library because it generates build scripts by analyzing your project and its dependencies, automating the creation of object files and archive files. CMake reads the CMakeLists.txt file, which specifies your project requirements and the necessary build steps. By defining the source files, target libraries, and executables in this file, CMake can automatically create the required object files, as well as the archive file (static library). This means, you don’t need to perform these steps manually.

When linking your program to a static library, the compiler first compiles all C source files into object files. Any external symbol (like a function or variable) referenced in those files remains undefined in the compiled object file. In this example, the main.c file has one external reference (ie add).

During the linking process, the linker searches for the definition of every undefined symbol in main.o in the object files contained in libint.a. The linker then finds that the add function is defined in add.o, so it copies the code from add.o into the final executable.

Please note: Since

main.cdoesn’t reference any code fromsub.c, the final executable doesn’t includesub.o. This point is essential because it means that in static linking, only the code that’s used from the library is copied into the executable.

Advantages of Static Linking

Following are some of the advantages of static linking:

- Portability: Static linking produces an executable binary that doesn’t have any dependencies. Once it’s generated, it can be run on other machines without needing to install any additional libraries.

- Performance: Static linking improves performance because, during the program execution, all program data is already loaded into memory.

- Control: Static linking provides control over the library versions that are being linked, helping to avoid bugs and incompatibilities that can arise from using different versions of libraries on different systems.

Disadvantages of Static Linking

While static linking has its benefits, there are also some disadvantages to consider:

- Increased file size and memory usage: Because static linking copies code from the static library into the executable, the executable file size is bigger. Additionally, statically linked programs consume more memory because they contain copies of the code and data from the libraries.

- Longer build times: Static linking requires longer build times because the linking happens at build time. This can be especially noticeable in large projects with many dependencies.

- Maintainability issues: If there is any change in the library, all the linked programs need to be relinked against the updated version of the library. This can become a burden for developers who have to ensure that all the programs that rely on the library are updated accordingly. In addition, since static linking creates a separate copy of the library code in each executable, it can be more difficult to keep track of which versions of the library are being used in different programs.

What Is Dynamic Linking?

Dynamic linking is a method of linking a program to a library at runtime rather than at build time. When you link a program to a library dynamically, the dependency information is stored in the executable as a reference to the library instead of the actual library code. As the program is executed, the operating system loads the dependent libraries into memory and resolves the symbols using them.

Libraries that are meant to be linked dynamically to targets are known as dynamic libraries, dynamically-linked libraries, or shared libraries. These libraries carry the file extension .so (short for shared object library), .dylib (short for dynamic library) on MacOS, and .dll (short for dynamic link library) on Windows.

During linking, these libraries are not included as a part of the executable binary, allowing the binary to be smaller in size than when using static linking. When the binary is executed, it looks up the dynamic library file using the path that was provided to it by the linker during the linking process and loads the required code from the library.

This allows for multiple targets to reuse the same dynamic library file by simply referencing it at runtime. However, this also means that the target executables that are linked to such dynamic libraries will not function correctly in the absence of these libraries on the target host, so you need to distribute such libraries just as you would distribute the executable binaries of your programs to your target users.

For example, imagine you’re developing a photo editing application that supports several filters. These filters are implemented in a separate dynamic library such as imagefilters.so, in the form of functions like applySepiaFilter and applyFishLens. With dynamic linking, your application can efficiently reference the necessary filter functions without needing to incorporate all the code in its executable file.

When a user starts the application, the operating system detects that the imagefilters.so library is required and loads it into memory before the main program starts executing. The filter functions are now available for use in your application as it runs.

Dynamic linking offers several advantages in this scenario. First, it helps to keep the photo editor’s executable file smaller and less complex by avoiding the need to include every filter’s code. Second, it allows you to easily update or add support for new filters by simply providing an updated dynamic library without modifying the editor’s core code. This modular approach not only simplifies program development but also makes it more flexible and easier to maintain for both developers and users.

Dynamically Linked Libraries

A key component of dynamic linking is the use of dynamically linked libraries. In this section, you’ll create a dynamic library and link it to a main program. This will give you a hands-on understanding of how to use dynamic libraries in your own projects.

Dynamic libraries are also called shared libraries. The term “shared” is used because multiple programs can use the same library, reducing the amount of redundant code and saving memory.

In the previous section you created a static library. With a few changes to the CMakeLists.txt file, you can create a dynamic library in place of the static library. Replace the contents of the CMakeLists.txt file with the following configuration that is documented inline:

# The minimum CMake version required to build this project

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.10)

# Project name

project(linking_demo)

# Create a dynamic library from the source files

add_library(libint SHARED add.c sub.c)

# Set the library output name as libint

set_target_properties(libint PROPERTIES OUTPUT_NAME int)

# Set the library output directory

set_target_properties(libint PROPERTIES LIBRARY_OUTPUT_DIRECTORY \

${CMAKE_CURRENT_BINARY_DIR}/lib)

# Add the include directory for the library to access necessary header files

target_include_directories(libint PUBLIC ${CMAKE_CURRENT_SOURCE_DIR})

# Create an executable using main.c and link it to the library

add_executable(main main.c)

target_link_libraries(main PRIVATE libint)Here, you made the following modifications:

- The

add_library()command creates a library from the source files. By passingSHAREDas the second argument, you specify that you want to generate a dynamic library. In comparison, when creating a static library, you pass aSTATICvalue. - You change the second invocation of the

set_target_propertiescommand and set the library output directory. In addition, you change the property name toLIBRARY_OUTPUT_DIRECTORYfromARCHIVE_OUTPUT_DIRECTORY. - You use

target_link_libraries()with thePRIVATEkeyword to link themainprogram withlibint.

Now, build the project:

$ cmake .

$ cmake --build .You should see the following output:

Scanning dependencies of target libint

[ 20%] Building C object CMakeFiles/libint.dir/add.c.o

[ 40%] Building C object CMakeFiles/libint.dir/sub.c.o

[ 60%] Linking C shared library lib/libint.so

[ 60%] Built target libint

Scanning dependencies of target main

[ 80%] Building C object CMakeFiles/main.dir/main.c.o

[100%] Linking C executable main

[100%] Built target mainPlease note: On macOS, the standard extension for dynamic libraries is

.dylibinstead of.so.

What Happens During Dynamic Linking?

In dynamic linking at build time, the executable file is equipped with information about the dynamic libraries that the program needs. When the program is run, the operating system examines the list of necessary dynamic libraries and attempts to load them accordingly. If any of these dependencies are not found or cannot be loaded, the execution fails.

Let’s take a look at how this works in the context of your project. If you’re on Linux, run the ldd command to see what dynamic libraries your program depends on like this (macOS does not have the ldd command, but the same concepts apply):

$ ldd mainOutput:

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffec69bb000)

libint.so => /home/abhinav/dev/linking_explained/dynamically_linked_libraries/lib/libint.so (0x00007fa1d8401000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007fa1d81f2000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007fa1d840d000)In the output you can see that the main program depends on quite a few dynamic libraries. The dependencies on linux-vdso.so.1, libc.so.6, and ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 are system dependencies added to all the programs in order to run them on Linux. You can also see the dependency on the library you created: libint.so, and next to it is the file path of the library.

When the program is run, the OS will try to load the library from that location. You can verify this by running the program as shown here:

$ ./main

$ echo $?

30Since the program doesn’t produce an output, you won’t see anything appear on the screen when you run it. However, it returns the sum of the global variables x (value 10) and y (value 20). You can verify the exit status of the program by running the command echo $?, and you should see the status as 30.

Now, let’s remove the dynamic library file from the lib directory and run the program to see what happens:

$ rm lib/libint.so

$ ./main

./main: error while loading shared libraries: libint.so: \

cannot open shared object file: No such file or directoryAs you can see, the OS is unable to load the libint.so dynamic library and the program fails to execute.

In general, the OS looks for dynamic libraries in a few standard locations such as

/lib,/usr/lib, and/usr/local/lib. This search path can be extended by setting an environment variableLD_LIBRARY_PATHon Linux, orDYLD_LIBRARY_PATHon macOS. Or you can generate binaries which have the path of the library hardcoded in the binary itself. In this case, the OS looks for that library only in that path, which is what CMake did in your project, as you saw in the output of thelddcommand where the full path of the library was embedded in the binary.

Advantages of Dynamic Linking

Following are some of the advantages of dynamic linking:

- Reduced file size: Dynamic linking produces smaller binaries as opposed to static linking since the code from the library isn’t copied into the binary during compilation. Instead, the symbols are dynamically resolved during runtime.

- Reduced memory usage: Dynamic libraries can reduce memory usage by allowing multiple programs in the system to resolve their symbols against the same copy of the library loaded into memory. This is more efficient than each program containing a copy of the same code in memory, which happens when multiple binaries are linked to the same static library, leading to higher memory consumption.

- Ease of update: When a library is updated, only the new version of the library needs to be installed, and the linked programs don’t need to be rebuilt. However, with static linking, all linked programs must be relinked.

Disadvantages of Dynamic Linking

Following are some of the disadvantages of dynamic linking:

- Performance overhead: Since the required libraries must be loaded into memory and all the symbols must be resolved before execution can proceed, it adds overhead to program execution, whereas static linking offers better performance because the resolution happens at build time.

- Versioning issues: If multiple programs require different versions of the same library, it can be hard to maintain them. In the case of static linking, each program has control over which version of the library they want to link against.

- Portability issues: Dynamically linked programs can make deployment more complicated, as it requires providing or separately installing dependencies for the end user. In contrast, static linking produces a binary that is free of dependencies. This is why many modern programming languages, including Go and Rust, default to producing statically linked binaries.

How to Choose Between Static and Dynamic Linking

As you can see, static and dynamic linking each have their own unique advantages, and choosing between them depends on the goal of your project. The following guidelines can help point you in the right direction.

In general, if you want to simplify deployments and if a larger binary size and increased memory usage are acceptable trade-offs, then static linking is the right choice. Static linking creates a stand-alone binary file that can be deployed and run without any dependencies. Moreover, it’s quick to start up.

If you expect several programs to be linked against the library and you need all of them to run concurrently, then you might want to select dynamic linking, as it results in an overall reduced memory footprint of those programs, especially if the library is large. For example, if you want to run a few machine learning models that depend on a GPU library, such as one of the NVIDIA libraries, dynamic linking reduces the amount of memory you use.

If you don’t expect your library to change frequently and the programs using it are not memory-intensive, static linking is the better choice.

Conclusion

In this article, you explored the concept of linking and its role in resolving symbols in a program. You learned that there are two types of linking: static, which occurs at build time, and dynamic, which occurs at runtime. You also discussed the advantages and disadvantages of each approach, highlighting that the choice between static and dynamic linking depends on the specific needs of the project.

For a deeper dive into linking, check out chapter 7 of Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective (third edition).

Earthly Cloud: Consistent, Fast Builds, Any CI

Consistent, repeatable builds across all environments. Advanced caching for faster builds. Easy integration with any CI. 6,000 build minutes per month included.