The Montréal Effect: Why Programming Languages Need a Style Czar

In this Series

Table of Contents

Here is a non-realistic scenario: You are choosing the programming language for what will eventually become something large. Picture a collection of services in a mono repo, with over 100 people working on it. To keep this extra unrealistic, let’s say you’re ignoring the usual constraints, like whether you can afford GC, or whether the problem fits well with a specific tech stack or whatever. it’s a thought experiment. Humor me. Based on my previous post, you’d correctly assume that I would want an expressive language aimed at experts. And I do. But there’s a big problem when things scale up in a flexible language. Too many coding styles, too many ways to program. You end up needing style-guides to nail down the right way to do things.

Which subset of C++ or Kotlin are you using? Are you using project.toml or requirements.txt? Your language now has gradual typing with Type Annotations. Do you want to adopt those or not? Are you going to use multi-threading, Tokio, or Async-std for concurrency?

The more expressive the language, the harder this is. This is where Go shines. It’s not just about gofmt, but also its standard library and the consistent way of doing things. In Kotlin, you’re left wondering: exceptions or Result for errors? But with Go, you know the drill. Look for err. Sure, it’s wordy, but it’s predictable.

Expressive languages are great, but they can be messy. You can have a language that’s rich and complex without a million ways to do the same thing. That’s what I want to show you. How do we keep the power but ditch the clutter? How do we avoid having 500 subdialects of the language? But before we dive into solutions, let’s talk Scala.

The Scala Problem

To highlight the problem, take Scala. A language I absolutely love, by the way. But it’s got this one big issue. There’s no idiomatic Scala. It’s way too flexible.

I can write a single file, calculator class and start with a Java style:

// Returns, braces and semi-colons

def getResult(): Double = {

return result;

}

def multiply(number: Double): Calculator = {

if (number == 0) {

println("Multiplication skipped: number is 0");

} else {

result = result * abs(number);

}

return this;

}Same class, same file, I can switch to a pseudo-Python style:

// significant whitespace, no returns, no semi-colons

def add(number: Double): Calculator =

result += abs(number)

this

def subtract(number: Double): Calculator =

result -= abs(number)

thisAnd then, when I call the whole thing, I can use no braces and no dots style. The Ruby DSL style:

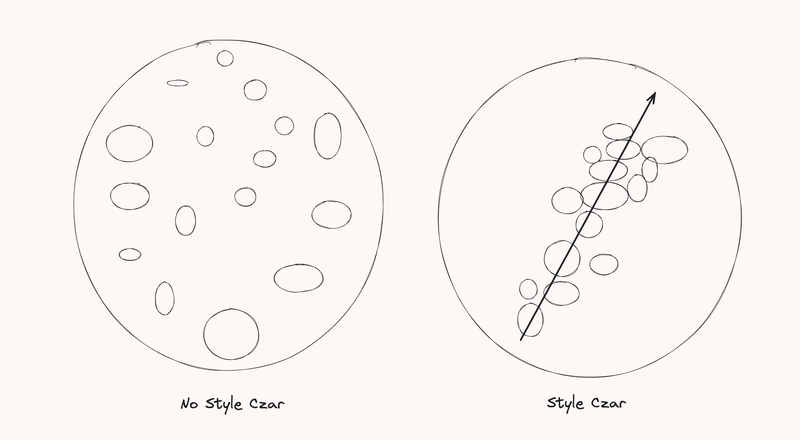

val calc = new Calculator add -5 subtract -3 multiply -2Hopefully, nobody’s stuck with code like this. You pick your dialect of Scala and you stick to it. But as code grows, it’s like Montreal. Every part of the city is different. On a long enough timescale, every quirk possible in your programming language will show up in your code.

Eventually, someone copies and pastes code in a different style. Maybe they like it better. Or in a new service, they do things their way. Or a junior mimics a library’s style from the docs. And style divergence starts1.

( Every Scala thread on hn has a comment from someone who inherited a Scala codebase that they are struggling to make sense of, in part because its in a foreign style. )

The Montreal C++ Problem

C++20 had a lot of good ideas, but lots of code predates that standard. And so drift occurs. You either don’t adopt the new way or you end up with a code base with more than one style. If you do the latter, you end up with the Montreal Problem. If you are doing work in the old-Montreal code section. It’s like a different dialect. You now need to know multiple dialects of the language and when and where to apply each one.

So, how do you evolve a language without splitting it apart? This gets trickier with a whole community involved. Big open-source projects often have their own style. The natural tendency towards divergence means it’s hard just to jump into existing codebases we aren’t familiar with because they’ve got their own style. And with that, the community fractures.

Style Guides Are Not Enough

Style Guides, especially if they can be machine-enforced, can help a lot at the level of a large code base. I think it’s great when languages can experiment with things. Maybe we don’t know if it totally makes sense to use types in Python everywhere yet or how much you should use generics in Go or whatever.

But for a specific project, we can set rules. Say, ‘this Python needs types’ or ‘Use generics in Go when you can.’ We set standards for testing libraries and build tools. And we attempt to enforce these rules with tooling where we can. But I think we can do even better at a language community level.

Codebase-specific style guides aren’t enough.

The Style Czar

When Scala 2.0 launched in 2006, internal DSLs were all the rage, and with Ruby on Rails leading the charge, Scala embraced a more fluid writing style. But times change and that style is no longer idiomatic Scala.

But how would you know that if you’re not in the right circles? Big ORM frameworks still use that style in their guides. The tricks for writing modern idiomatic Scala are trapped in the minds of the community leaders. That’s not great.

We need a Style Czar. Someone in the language community who can say that this is idiomatic Scala 2.1

def ABSOrSeven(maybeNumber: Option[Int]): Int = {

if (maybeNumber.isDefined) Math.abs(maybeNumber.get)

else 7

}But in Scala 3.1, this is preferred:

def ABSOrSeven(maybeNumber: Option[Int]): Int = {

maybeNumber.map(Math.abs).getOrElse(7)

}What I’m suggesting is that every release of a language should come with a style-guide. No one has to follow it; companies and projects may diverge, and the standard might be highly contested; but it should exist and be written down somewhere.

Idiomatic Python

Python folks love their Pythonic code, the zen of Python, and PEP 8. And that is what I’m thinking about, but evolving over time, and with a larger scope. I think the language creators need to not just create the language but be shepherds for emerging standards in how programming is done in the language. They need to talk to us, tell us: do this, not that. And it should be a conversation, with debates, with tools to help us follow the rules.

This standard will keep changing, right? It will evolve as the language does. Maybe type annotations, when they first roll out in Python, are considered experimental. But once everyone is comfortable with them and thinks they are a good idea, Python should take a stance and say type annotations are required in pythonic code. Or say that they are not. But please have an opinion. As the language grows and the community starts to diverge in various ways, the scope of the style document should expand as well.

Here’s an example: Python has to pick a lane with package managers and virtual environments. I think poetry and project.toml should be the way forward, and others have a requirements.txt-for-life tattoos. But any solution would be better than what we have now.

We need someone in charge to step up. “Okay, everyone, we’re standardizing on Hatch for Python packaging. If you’ve got issues with Hatch, speak up. We’ll look into them. But just so you know, we’re aiming to make Hatch the go-to for Python 3.16.”

This goes for testing frameworks, standard libraries, and even how we handle concurrency. Language communities love to experiment and explore. But after the exploring, we need to come together. And that’s where the language creators step in. They’re the ones who can really make it happen.

Expressiveness

Ok, so how does this tie to being expressive? Well, if your language is on the ‘expert readability’ train, you probably have a bunch of features and aren’t afraid to add new ones. The problem is you slowly end up in a world where each codebase is written in its own subset of the language. So, deprecate things. Sure, keep old stuff for compatibility, but let’s nudge everyone towards a common standard.

The fact you are evolving the language implies you have an opinion about what great code looks like. Tell us! Write it down. Talk it out with the community. Using macros is not idiomatic in C++20. Using if’s to check the types of a returned object is not idiomatic Kotlin 1.17. Don’t use explicit returns in Scala. And so on.

This way, there’s always a target of what great code looks like. Even if that target moves, every sane code base is just at a specific point along that journey to the latest and grandest code style.

In other words, you can end up in a world where all idiomatic Java 20 code is as uniform as Go, but to get there, you have to take a stance on when it’s appropriate to use the streams API and when not. I mean, maybe you never quite get there: one person’s clear stream processing one-liner is another man’s spaghetti code, but I really think we could do better at converging on what we want the language to look like.

End the Butter Battles

This brings up a bunch of questions. How much of this can be tool-enforced? When should a popular library be canonized? How much style guidance is too much and stifles innovation? I don’t really know. Just start with something, like a version of Python PEP 8, and evolve and expand it over time.

If something is a community norm, write it down. If the community is fighting over whether to eat toast butter side up or butter side down, flip a coin, make a call, and move on. The community will be better for it.

Show us the way, Style Czar!

This is just an easy to show example. If I were the style Czar, then yes

Don't use explicit returns or semicolonswould be a rule. But so wouldDon't pattern match if you can use fold or mapandDon't use fold if you can use getOrElseandDon't do manual recursionandDon't use actors unless you have a really good reasonandDon't write custom operators. Just don't. Really.and so on and on. Lot’s of features are only valuable in specific circumstances.↩︎