Showboaters, Maximalists and You

In this Series

Table of Contents

Following from Rust, Ruby, and the Art of Implicit Returns

The Java I learned in university was Java 1.X, and the concepts were simple. “In Java, everything is an object,” I was told.

So you’d do something like this a lot:

interface Greeter {

void greet();

}

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Greeter greeter = new Greeter() { // <- Anonymous Inner Class

@Override

public void greet() {

System.out.println("Hello, world!");

}

};

greeter.greet(); // Outputs: Hello, world!

}

}I wrote a lot of Java Swing at the time. So I felt like Java was a lot about writing Anonymous Inner Class like this:

button.addActionListener(new ActionListener() {

@Override

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e) {

JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(frame, "Button was clicked!"));

}

});Now Java has lambdas, so I assume I could now write:

button.addActionListener(e ->

JOptionPane.showMessageDialog(frame, "Button was clicked!"));And my greeter could be something like:

Greeter greeter = () -> System.out.println("Hello, world!");This is so much nicer—less boilerplate to write and fewer places for bugs to hide. I feel the same way about if expressions.

if(x > 7) {

y = 5

} else if(x > 5) {

y = 4

} else {

y' = 3

}y = if(x > 7) {

5

} else if (x > 5) {

4

} else {

3

}There are some redundancies in the first, and because of that, it’s possible to have errors. You learn to skim over the boilerplate parts of code, but those parts can have bugs, hence the error in the first version. The slightly shorter expression-based code has less room for error.

I’m not a C++ programmer, but C++’s constexpr is another great example of improved expressiveness and readability. Doing things at compile time previously involved macros or templates, but now you can use constexpr:

constexpr double circleArea(double radius) {

return 3.14159 * radius * radius;

}

constexpr double area = circleArea(5.0); But if syntactical sugar and more language features are a net win for experienced users, why did Java succeed so much when it was pretty simple? Why is Go succeeding? Why was there skepticism when Swift came out? Why so much aversion to C++?

There are lots of factors. One is a steep learning curve, but another is the showboaters.

Learning Curve

Expressivity has a cost. These concepts add complexity and make learning the language harder.

First, I was taught ‘In Java, everything is an object’ and then ‘In Java, everything is an object, except primitive types’, and then we had to add some footnote that lambda is just syntax for an object with one method that is made on the fly. And so on, we keep adding on little exceptions or wrinkles. Even when all the concepts fit together nicely, there is still just strictly more for a newcomer to learn.

But it’s worth it. Learning is a cost you just pay once, and you get a more expressive language in return. Beginner readability suffers, but the readability that matters is the readability of an experienced language user, and removing repetitive boilerplate improves that.

However, complexity can compound.

Compounding Complexity

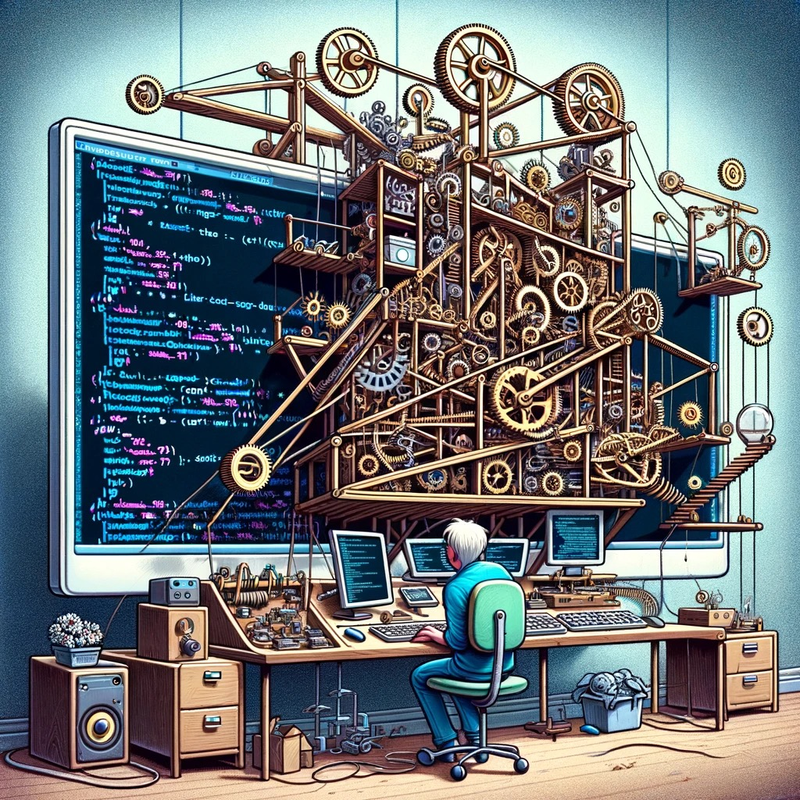

I can show you each language feature of a language in isolation and how it makes things better. But real world code will likely be more complex. In practice, experts use many of the language features together all at once. And to an outsider, this can be pretty confusing.

In an expressive enough language and with a group of strong developers, you can end up with something like The Focused in A Deepness In The Sky:

Reynolt cut the audio. “They went on like this for many days. Most of it is a private jargon, the sort of things a close-bound Focused pair often invents.”

Nau straightened in his chair. “If they can only talk to each other, we have no access. Did you lose them?”

“No. At least not in the usual way.”

The book is excellent, and without saying too much, in it groups of experts obsessed with a problem can spin off into an internal jargon no outsider can make sense of. In the worst case, they may come up with powerful answers to important questions, but the whole thing is incomprehensible to the outsider.

And this is sort of what happens when a developer most familiar with Java 8 inherits a Scala program that does a relatively simple task and opens it up to find it written in some functional effect system.

def program: Effect[Unit] = for {

h <- StateT[Effect1, Requests, String]((requests: Requests) =>

ReaderT[Effect0, Config, (Requests, String)]((config: Config) =>

EitherT(Task.delay(

((requests, host.run(config))).right[Error]

))))

p <- StateT[Effect1, Requests, Int]((requests: Requests) =>

ReaderT[Effect0, Config, (Requests, Int)]((config: Config) =>

EitherT(Task.delay(

((requests, port.run(config))).right[Error]

))))

_ <- println(s"Using weather service at http://\$h:\$p\n")

.liftM[ErrorEither]

.liftM[ConfigReader]

.liftM[RequestsState]

_ <- askFetchJudge.forever

} yield ()This example is a little over the top, but the reaction is a real thing that happens when someone first encounters code from a language using complex syntax, advanced concepts, and concise code all at once.

This isn’t just an Functional Programming thing, either. Here’s some simple to understand Go code for leet code 2529 :

func maximumCount(nums []int) int {

var pos, neg int = 0, 0

for _, e := range nums {

if e > 0 {

pos++

} else if e < 0 {

neg++

}

}

if pos > neg {

return pos

} else {

return neg

}

}Code Report’s C++ solution requires knowledge of count_if and how C++ does lambdas:

int maximumCount(vector<int>& nums) {

return std::max(

std::ranges::count_if(nums, [](auto e) { return e > 0; }),

std::ranges::count_if(nums, [](auto e) { return e < 0; })

);

}And the Rust solution requires knowledge of iterators, filters, and more.

pub fn maximum_count(nums: Vec<i32>) -> i32 {

let pos = nums.clone().into_iter().filter(|e| *e > 0).count() as i32;

let neg = nums.into_iter().filter(|e| *e < 0).count() as i32;

std::cmp::max(pos, neg)

}This Scala, C++, and Rust code may all cause a particular reaction in the unfamiliar: ‘why all the concepts used, when the solution could be so simple’. But the examples are quite different. The Scala one is showboating, and others are not1.

Crafting Clarity

All maximum count versions use the constructs of the language to express the algorithm straightforwardly. They require familiarity with the concepts, but they are an expressiveness win.

MaximumCount =. 0&(<./.>.) (+//)The Scala solution is actually where legit complaints can come. In most cases, if you are inheriting code like that – code that reads a host and a port for a weather service and then gets the forecast for your city - if you inherit code like that, and it’s not in the context of research on chaining effects - then someone is showboating. It’s a simple problem expressed in a complex way. Maybe to show off or maybe for self-entertainment. Sometimes, people make things complex to keep themselves interested.

It can be hard to discern the reasoning behind a solution without all the context.

Pure Show Boating Is Rare

func main() {

numbers := []int{1, 2, 3}

sumChan := make(chan int)

go func() {

sum := 0

for _, num := range numbers {

sum += num

}

sumChan <- sum

}()

totalSum := <-sumChan

fmt.Printf("Total Sum: %d\n", totalSum)

}I think pure showboating is rare and rarely totally intentional. If you know all the intricate features of a language, then, you might reach for those features when you create a solution. And it might not be apparent that this will make newcomers struggle; it’s just the obvious way to structure the solution. It’s the curse of knowledge.

And add to that that most people using an expressive language enjoy the power they wield. And if you learn about a new feature, library, technique, or whatever, you might want to use it. And maybe sometimes you use it when it’s not strictly needed. And you wake up one day, and no one outside your group understands your code.

So use some constraint. Everybody goes through a maximalist phase where they use some feature more than they should, pushing a concept to its limits. But maybe do that in a side project and not the thing someone else will inherit.

...

from y in Enumerable.Range(0, screenHeight)

let recenterY = -(y - (screenHeight / 2.0)) / (2.0 * screenHeight)

select from x in Enumerable.Range(0, screenWidth)

let recenterX = (x - (screenWidth / 2.0)) / (2.0 * screenWidth)

let point = ...

let ray = // And so on for 60 lines

...If you’re in a group, and you’ve developed a house style for solving problems, that might be great. But if a new person who is bright and eager joins and you struggle to get them up to speed, that could be a reasonable signal to reflect on why that is the case.

Give It A Chance

The other side of this is tricky as well. If you encounter code or even a whole programming language where the code seems too clever by half, I think you should hold your opinion for a bit.

It’s easier to judge a given solution once you know the idioms in use and the way various features work and interact. That foreign-looking solution may be very well encapsulated in the expressiveness of the language in a way that is just unfamiliar to you right now. Maybe, a solution with just ifs and loops would be so lengthy that it’d be difficult to hold in your head all at once.

Maybe not, though. Some people look for challenges and create them where none exists. But… if you don’t know the idioms and patterns of the language, it might be too early to make that call.

Programming language features can make code clearer. They can improve readability. But each feature is also a new tool for writing horrible code. Is that worse than people writing horrible code with other simpler constructs? It might be, but it’s hard to judge a solution if you don’t know the language.

If you’re going to spend your career doing this, it makes sense to keep learning. To use a language that allows experts to cleanly solve problems. But yeah, just don’t leave piles of esoteric code around for others to inherit.

This example is just for fun. Pawel improves upon it in his talk. I love Scala, but trying to write Haskell in Scala, even when its a bad fit, is endemic. I’ve been guilty of that myself.↩︎