Beating TimSort at Merging

In this Series

Table of Contents

Here is a problem. You are tasked with improving the hot loop of a Python program: maybe it is an in-memory sequential index of some sort. The slow part is the updating, where you are adding a new sorted list of items to the already sorted index. You need to combine two sorted lists and keep the result sorted. How do you do that update?

Yes, this sounds like a LeetCode problem, and maybe in the real-world you would reach for some existing sorted set data structure, but if you were working with python lists, you might do something like this1:

def merge_sorted_lists(l1, l2):

sorted_list = []

while (l1 and l2):

if (l1[0] <= l2[0]): # Compare both heads

item = l1.pop(0) # Pop from the head

sorted_list.append(item)

else:

item = l2.pop(0)

sorted_list.append(item)

# Add the remaining of the lists

sorted_list.extend(l1 if l1 else l2)

return sorted_listPython has a built-in method in heapq.merge that does this. It takes advantage of the fact that our lists are already sorted, so we can get a new sorted list linear time rather than the n*log(n) time it would take for combining and sorting two unsorted lists.

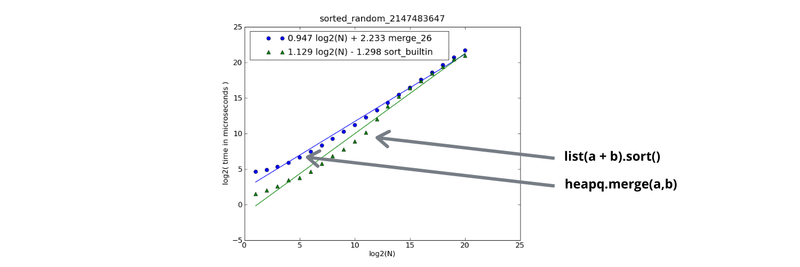

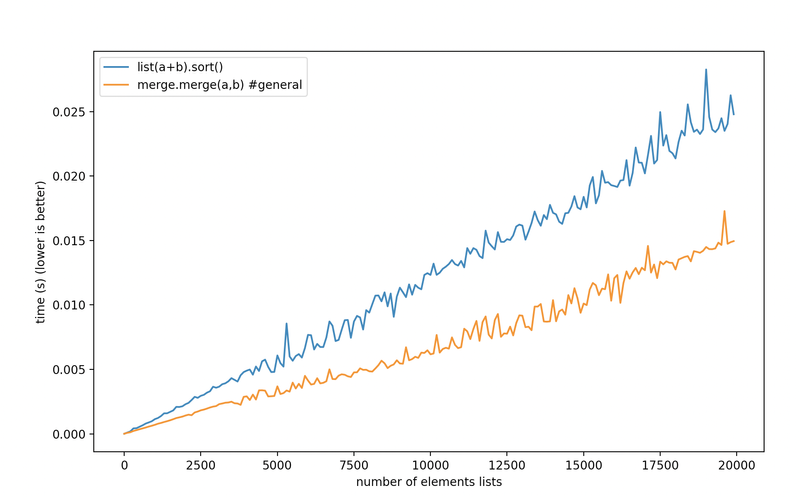

Imagine my surprise then when I saw this performance graph from Stack Overflow:

Sorting the list is faster than just merging the list in almost all cases! That doesn’t sound right, but I checked it, and it’s true. As Stack Overflow user JFS puts it:

Long story short, unless

len(l1 + l2)>= 1,000,000 use sort

The reason sort beats merge in most cases is because of a man named Tim Peters.

TimSort

Python’s list.sort is the original implementation of a hybrid sorting algorithm called TimSort, named after its author, Tim Peters.

[Here is] stable, natural merge sort, modestly called Timsort (hey, I earned it

). It has supernatural performance on many kinds of partially ordered arrays (less than lg(N!) comparisons needed, and as few as N-1), yet as fast as Python’s previous highly tuned sample sort hybrid on random arrays.

Timsort is designed to find runs of sequential numbers and merge them together:

The main routine marches over the array once, left to right, alternately identifying the next run, then merging it into the previous runs “intelligently”. Everything else is complication for speed, and some hard-won measure of memory efficiency.

This is why (x + y).sort() can be surprisingly fast: once it finds the sequential runs of numbers, it functions like our merge algorithm: combining the two sorted lists in linear time.

Timsort does have to do extra work, though. It needs to do a pass over the data to find these sequential runs, and heapq.merge knows where the runs are ahead of time. Timsort overcomes this disadvantage by being written in C rather than Python. Or as ShawdowRanger on Stack Overflow explains it:

CPython’s

list.sortis implemented in C (avoiding interpreter overhead), whileheapq.mergeis mostly implemented in Python, and optimizes for the “many iterables” case in a way that slows the “two iterables” case.

This means that if I drop down to C and write a C extension I should be able to beat Timsort. This turned out to be easier than I thought it would be2.

The C Extension

The bulk of the C Extension, whose performance I’m going to cover in a minute, is just the pop the stack algorithm discussed before, but using an index to point to the head of the stack:

//New List

PyObject* mergedList = PyList_New( n1 + n2 );

for( i = 0;; ) {

elem1 = PyList_GetItem( listObj1, i1 );

elem2 = PyList_GetItem( listObj2, i2 );

result = PyObject_RichCompareBool(v, w, Py_LT);

switch( result ) {

// List1 has smallest, Pop from list 1

case 1:

PyList_SetItem( mergedList, i++, elem1 );

i1++;

break;

case 0:

// List2 has smallest, Pop from list 2

PyList_SetItem( mergedList, i++, elem2 );

i2++;

break;

}

if( i2 >= n2 || i1 >= n1 )) {

//One list is empty, add remainder of other list to result

...

break;

}

}

return mergedList;The nice thing about C extensions in Python is that they are easy to use. Once compiled, I can just import merge and use my new merge method:

import merge

# create some sorted lists

a = list(range(-100, 1700))

b = list(range(1400, 1800))

# merge them

merge.merge(a, b)Testing It

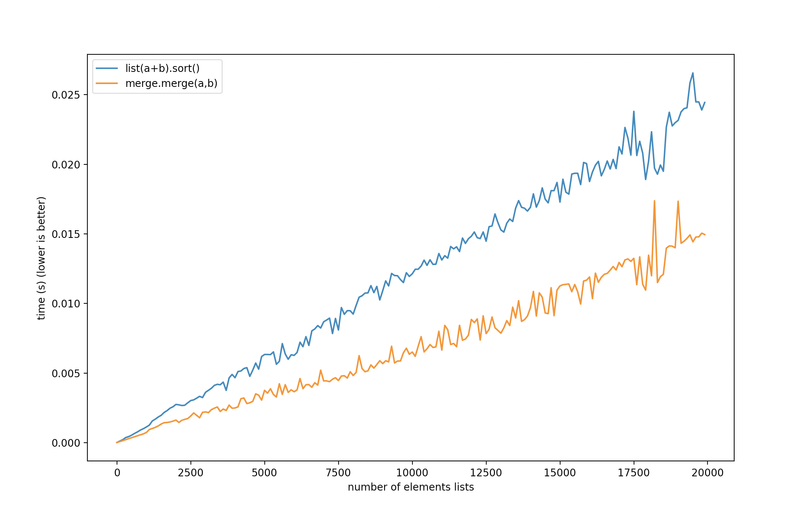

Testing my new merge with a list of integers and floats, we can see that we are beating Timsort, especially for long lists:

import merge

import timeit

a = list(range(-100, 1700))

b = [0.1] + list(range(1400, 1800))

def merge_test():

m1 = merge.merge(a, b)

def sort_test():

m2 = a + b

m2.sort()

sort_time = timeit.timeit("sort_test()", setup="from __main__ import sort_test", number=100000)

merge_time = timeit.timeit("merge_test()", setup="from __main__ import merge_test",number=100000)

print(f'timsort took {sort_time} seconds')

print(f'merge took {merge_time} seconds')timsort took 3.9523325259999997 seconds

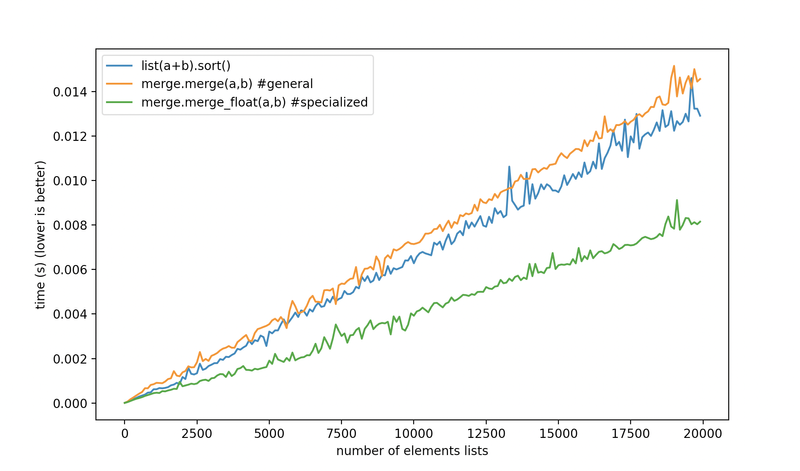

merge took 3.0547665259999994 secondsGraphing the performance we get this:

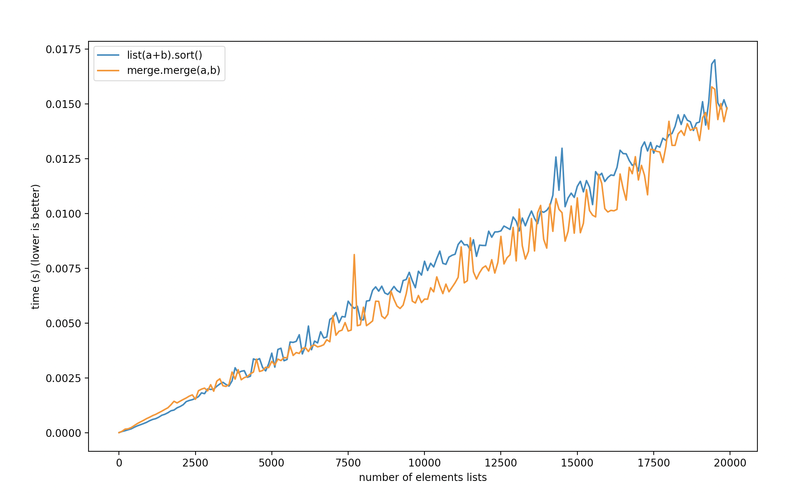

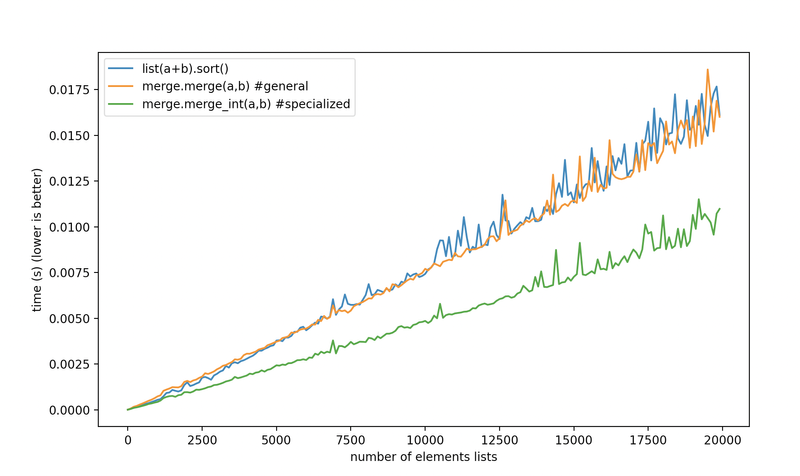

But if we switch to a list of only integers sort is beating us for small lists and even on big lists our performance improvement is thin at best:

int or all float we lose our advantage.

What is going on here?

Timsort’s Special Comparisons

It turns out that Timsort has some extra tricks up its sleeves in the case of a list of integers. In that initial pass over the list, it checks the types of the elements, and if they are all uniform it tries to use a cheaper comparison operation.

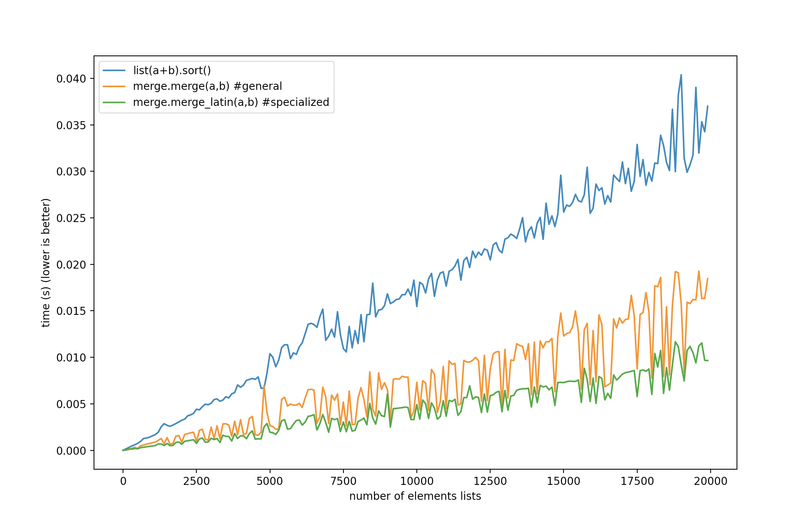

Specifically, if your list is all longs, floats, or Latin strings Timsort will save a lot of cycles on the comparison operations.

Learning from Timsort we can bring in these comparison operations ourselves. We don’t want to do a full pass over the list, or we will lose our advantage, so we can just specialize our merge by offering separate calls for longs, floats, and Latin alphabet strings like so:

//Default comparison

PyObject* merge( PyObject*, PyObject* );

//Compare assuming ints

PyObject* merge_int( PyObject*, PyObject* );

//Compare assuming floats

PyObject* merge_float( PyObject*, PyObject* );

//Compare assuming latin

PyObject* merge_latin( PyObject*, PyObject* )Beating TimSort

Doing that, we now can finally beat Timsort at merging sorted lists, not just when the list is a heterogeneous mix of elements, but also when it’s all integers, or floating-point numbers, or one byte per char strings.

int.

float.

The default merge beats Timsort for heterogeneous lists, and the specialized versions are there for when you have uniform types in your list, and you need to go fast.

TimSort Is Good

There, I have beat Timsort for merging sorting lists, although I had to pull in some code from TimSort itself to get here. I’m not sure how valuable this is: if you need to go fast, you might not choose Python, but it was a fun learning project.

Also, I learned that dropping down to C isn’t as scary as it sounds. The build steps are a bit more involved, but with the included Earthfile, the build is a one-liner and works cross-platform. You can find the code on GitHub and an intro to Earthly on this very site, and with that example, you can build your own C extension reasonably quickly.

The surprising thing, though, is how good Timsort still is. It wasn’t designed for merging sorted lists but for sorting real-world data. It turns out real-world data is often partially sorted, just like our use case.

Timsort on partially sorted data shows us where Big O notation can misinform us. If your input always keeps you near the median or best-case performance, then the worst-case performance doesn’t matter much. It’s no wonder then that since its first creation, Timsort has spread from Python to JavaScript, Swift, and Rust. Thank you, Tim Peters!

Practically, you might not want to use pop, but just track an index of where the head of the stack should be, like the C code shown later.↩︎

It was easier because my teammate Alex has experience writing C extensions for Python, so by the time I had found the Python header files, Alex had already put together a prototype solution.↩︎